Restorative justice is already happening. But how can genealogists and family historians contribute and make even more of a difference?

Reparations is a dirty word. It’s heavily soiled, drug through the mud. It needs to be bleached, sanitized, and dried in the sun. It’s a term that polls badly. Most people hear the word and think of an ATM that won’t stop spitting out money for African Americans or of programs that only elevate Blacks and while everyone else suffers. Even our elected officials can’t even come together to get a bill through the House that will “examine slavery and discrimination in the colonies and the United States from 1619 to the present and recommend appropriate remedies.”

But what if I told you that reparations efforts and programs already exist all over the country? What if I told you that universities, corporations, and private citizens were already practicing restorative and transformative justice for past wrongs connected to the enslavement of the ancestors of African Americans and that these things are totally a form of reparations?

Restoration of Identity

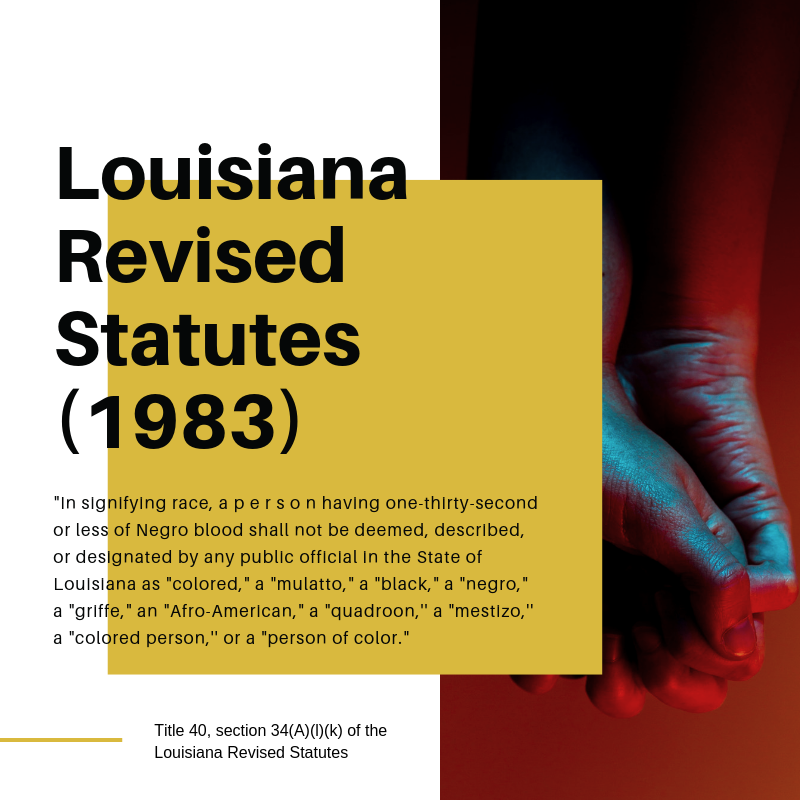

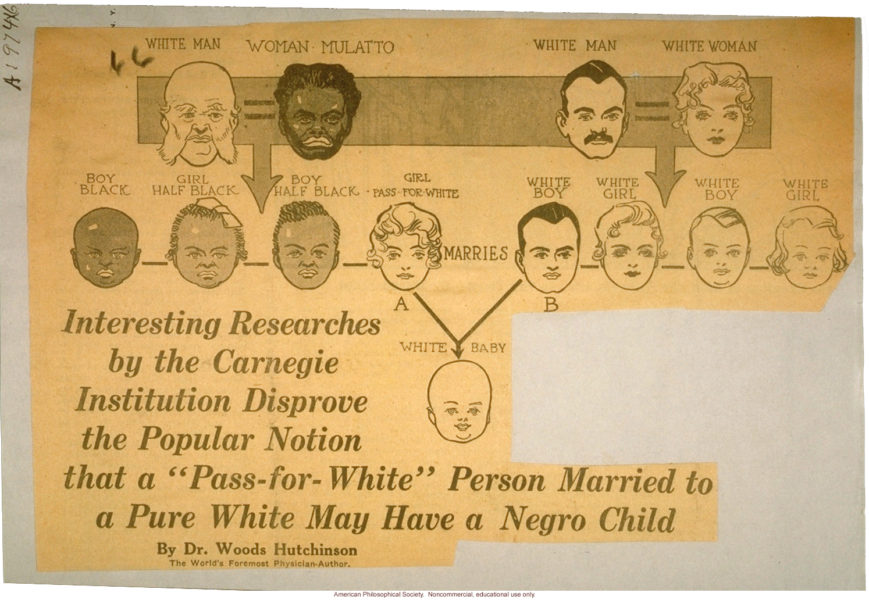

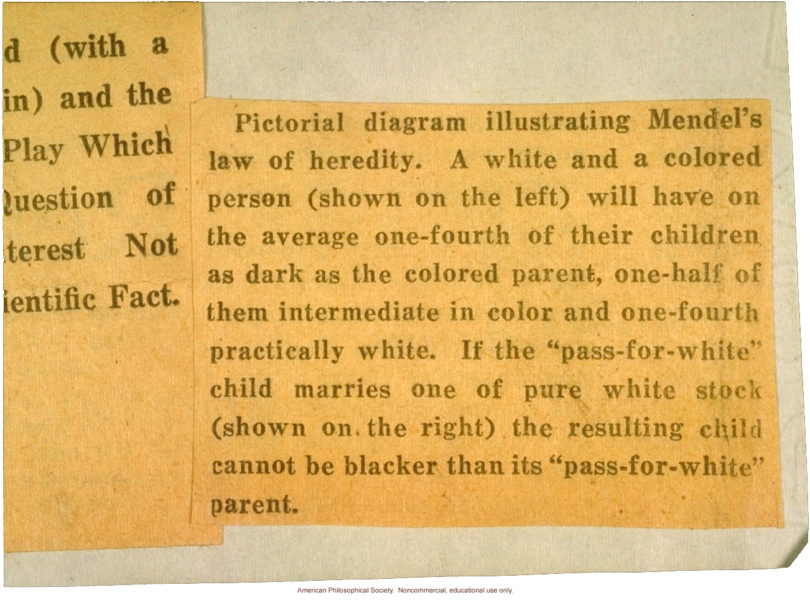

The identity of African Americans is always being questioned. Always. From the ridiculous caste system established in states like Louisiana to legally defining “Colored” people in Virginia, it has always seemed like the system – and those in power – have been busy defining who we are. Eugenics, and it’s byproduct genealogy, are at the center of this. As a result, our very legitimacy is always in limbo.

It was a deliberate choice to bring our ancestors here. Capitalism was at the heart of the complex root system of a tree that grew leaves of different shades of slavery throughout the country. On other hand, as a descendant of those captured and worked for free, it doesn’t appear to me that those who planted that tree really thought out all the scenarios once their pet economic project played itself out. It may have been impossible for them to do so. Hindsight can be a hell of an elixir.

I cannot ever think of a time in U.S. history where African Americans existence was ever 100% completely lawful, in word (read that the law) and deed. Even now. Yes, the social and legal status of the enslaved was well documented on paper, but that documentation, when looked at on a national scale, did not fully legislate their humanity. States rights, right? Unfortunately, the same could be said even now. The word/law mostly reflects our humanity but the deeds supporting such, from the government to private citizens, are so inconsistent when the point shouldn’t ever be argued.

When the very fact of our existence in the U.S. is treated as lawful and its complete origins and missteps are acknowledged, our identity can no longer be questioned. In 2019, this has never happened. The only way to shine a light on that is to atone the centuries of false information and correct the record with the truth. Genealogy and family history are a way to do that.

Genealogy and Family History Can Be Forms of Restorative Justice

Millenials are more open to the idea of slavery reparations. This makes sense because they are more diverse than predecessor generations and by virtue of that they are researching more than one type of ethnic group when they become interested in their family history. It’s why experienced researchers have seen so many within our lists of DNA matches. These young people are hungry for the information and it doesn’t matter the race or ethnic group of the folks they’re looking for.

Let’s dig into this deeper. The roots of our own industry are tainted by the pseudoscience of eugenics whose aim was to improve humanity and rid it of certain populations in an effort to protect it. Genealogy was the tool used to filter people in and out of grace. People of color being involved in the genealogy industry, either as a novice or a professional, goes completely against the racial ideology at the time genealogy was embraced and against the origins of the study.

Involvement now allows people of color to perform their own atonement on behalf of their ancestors who were considered disposable and their lives unimportant. It’s a proactive way of re-establishing identity while enhancing the knowledge of legacy for future generations.

The system of enslavement within the U.S. made it impossible to research the enslaved without researching their former slaveholders. No one can truly be successful in doing this research any other way. Just as the descendants of the formerly enslaved are restoring the voices of their ancestors, the descendants of those former enslavers can also do that. That, on both ends, is restorative.

According to Merriam-Webster, reparations is defined as

“the act of making amends, offering expiation, or giving satisfaction for a wrong or injury.”

Accurately and humanely telling the stories of all ancestors who lived during the slavery era is a form of restorative justice, but we’ve got to move beyond the acknowledgment phase.

Source: American Philosophical Society, 1915, side A. Eugenic Archives.

Words + Actions = Results

I’ve been contacted A LOT by the descendants of former slaveholders asking what they should do when they come across documents in their family’s possessions or online as they research. They want to move beyond the words and into action. I’ve suggested everything from creating a free blog where you post your documents, to donating them to an archive or university, to posting on social media, to tracking down descendants, and more. It’s all a personal choice, but if we’re speaking about it truthfully, based entirely on definitions, it’s a form of reparations.

I know that folks reach out to me because it seems intrinsic to them that people of color know what to do in this scenario and they don’t want to come across wrong. But the trauma and experiences are in ALL of our bodies, some of us have just been able to push those things down for decades, if not centuries. Empathy doesn’t cost a thing. Just as someone can contribute monthly to the ACLU in defense of immigrants, they can also do the following for people of color:

- volunteer to index or catalog records of importance;

- re-write your county history to include us;

- ALWAYS address the experience of people of color in the organizations you are affiliated with;

- illuminate the myriad of ways the entire country was involved in the system of slavery;

- try to research an African American family – without expectation for compensation – and share with your community what you learned in the process;

- respond and offer to help when a person of color tries to connect with you because you share DNA with them;

- create a project to transcribe inventories mentioning the enslaved in your counties/parishes of interest; and more.

These are just a few acts of restorative justice that don’t involve an endlessly spouting ATM or programs that some view as unfair. They correct the largely inaccurate narrative of slavery and the multitude of misinformation about the lives of African Americans and most importantly, help restore legitimacy and legacy. These things can done by regular people who aren’t famous, with no need for degrees or credentials. Do you know how much influence you have in your own family and social circles as you pass on what you learned after an act of restoration?

No one should be waiting for a corporate sponsor; we have the tools and we have the knowledge. It’s time to stop waiting for “someone” to change the story and make things right. We have billions of historical documents along with DNA to guide the journey.

Let the words of atonement be spoken, the actions of restoration take place without fear, and the results be fruitful, and a blessing, to everyone.

Below is a short list of news stories, existing projects, groups, and corporations that highlight the type of work that is needed. Many of these changes were made as a result of voices outside these places advocating on behalf of the voiceless. Keep that in mind as you ponder what you’ll do.

- Descendants of slave & slave owner discover kinship, USA Today, January 13, 2018

- ‘This is surreal’: descendants of slaves and slaveowners meet on US plantation, The Guardian, November 16, 2017

- “My ancestor owned 41 slaves. What do I owe their descendants?” America: The Jesuit Review, November 28, 2018

- “Slave-owner’s descendant gives away plantation,” BBC News, June 9, 2013

- “Descendant Of Slave Owner: Lynching Memorial Brings To Light A ‘Buried Narrative'”, NPR, April 28, 2018

- “Descendants of slaves and slave owners share experiences,” Courier Journal, January 2, 2015

- “In Franklin, Descendants Of A Slave And Slaveowner Talk About Their Shared History,” Nashville Public Radio, January 12, 2016

- “Black descendant of white slave owner celebrates Juneteenth,” Fort Bend Herald, June 19, 2018

- Interview: Bermudian Slave Owner Descendant, Bernews, June 24, 2011

- “My shameful secret: an ancestor of mine was a slave owner,” The Independent, July 15, 2015

- “Descendant of slave, slave owner forge friendship with a message,” WRAL, September 4, 2015

- “Descendant of MU founder atones for family’s slave-owning past,” The Missourian, January 20, 2014

- “Descendants of slave, owner strike a chord at city gathering,” New Haven Register, July 20, 2009

- “Descendants of slave owner, one of his slaves gathering to receive honor,” Myrtle Beach Online, July 31, 2014

- “Descendants of former slave will dedicate monument at his gravesite in Mount Holly,” Charlotte Observer, July 4, 2014

- “Slave descendants meet owner descendant at family reunion,” SC Now, July 31, 2014

Whitney Plantation

“Within the boundaries of the “Habitation Haydel”, as the Whitney Plantation was originally known, the story of the Haydel family of German immigrants and the slaves that they held were intertwined.

In 2014, the Whitney Plantation opened its doors to the public for the first time in its 262 year history as the only plantation museum in Louisiana with a focus on slavery.

Through museum exhibits, memorial artwork and restored buildings and hundreds of first-person slave narratives, visitors to Whitney will gain a unique perspective on the lives of Louisiana’s enslaved people.”

Monticello, plantation home of President Thomas Jefferson

“Daughter, mother, sister, aunt. Inherited as property. Seamstress. World traveler. Enslaved woman. Concubine. Negotiator. Liberator. Mystery.

Sally Hemings (1773-1835) is one of the most famous—and least known—African American women in U.S. history. For more than 200 years, her name has been linked to Thomas Jefferson as his “concubine,” obscuring the facts of her life and her identity. “ Click here for additional news coverage. Click here for the Plantation and Slavery exhibit.

The Hermitage, plantation home of President Andrew Jackson

Black History Month Memorial Service: “An annual commemoration of those enslaved at The Hermitage and throughout the country. Held at The Hermitage Church. The service concludes as attendees join in a procession to the slavery memorial “Follow the Drinking Gourd” located behind the church. 150 flowers will be laid, marked with the names of all those known to have been enslaved at The Hermitage. Click here for The Hermitage Slavery Exhibit.

Montpelier, plantation home of President James Madison

“Over the course of the Madison family’s time at Montpelier there were over 300 enslaved individuals who lived on the property. Men, women, and children worked tirelessly to keep the Madison plantation up and running such that James and Dolley could carry out their business. We pay homage to those in the enslaved community through our ongoing slavery interpretation, and our new groundbreaking exhibition, The Mere Distinction of Colour. We’re thankful to our active descendant community for helping us tell a more complete American story and sharing their familial histories with us.”

The Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project at Northeastern University School of Law

“…conducts research and supports policy initiatives on anti-civil rights violence in the United States and other miscarriages of justice during the period 1930-1970. CRRJ serves as a resource for scholars, policymakers, and organizers involved in various initiatives seeking justice for these crimes.”

Railroad Ties – Ancestry and Sundance TV

“Six descendants of fugitive slaves and abolitionists come together in Brooklyn to discover more about their lineage. Documenting each person learning about their ancestors, and featuring renowned historian, Henry Louis Gates Jr., the film interweaves powerful personal moments with contextual historical anecdotes.”

Jack Daniels and Nearest Green

“There is an interesting picture that hangs in Mr. Jack Daniel’s old office. It’s a picture of Mr. Jack taken with his Distillery crew. What makes the portrait so intriguing is the gentleman sitting immediately to Jack’s right, an African-American worker. Given the time period when this photograph was taken – around the 1900s – and the racial divide that permeated the American South, it’s intriguing to see an African-American man seated beside the proprietor of a business. But their proximity to one another in this photo underscores the remarkable relationship that is at the heart of how Jack came to make whiskey.

The man in the photograph above, we have reason to believe, is George Green. Along with being Jack’s friend, George was also the son of Nathan “Nearest” Green. And it’s Nearest Green, along with the Reverend Dan Call, who taught Jack Daniel about making whiskey at a still owned by the Lutheran minister.” Click here for additional news coverage.

Discover Freedmen – FamilySearch

To help bring thousands of records to light, The Freedmen’s Bureau Project was created as a set of partnerships between FamilySearch International and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society (AAHGS), and the California African American Museum.

The project began on Juneteenth (June 19) 2015 and with the help of more than twenty-five thousand volunteers, was completed on June 20, 2016. As a result of the tireless effort of thousands, the names of nearly 1.8 million men, women and children are now searchable online. Now that the images have been indexed, millions have access to the names of their ancestors, allowing individuals to build their family trees and connect with their heritage.”

Georgetown Slavery Archive and GU 272 Descendants Association

“The Georgetown Slavery Archive is a repository of materials relating to the Maryland Jesuits, Georgetown University, and slavery. This project was initiated in February 2016 by the Archives Subgroup of the Georgetown University Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation and is part of Georgetown University’s Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation initiative.” GU 272 Descendants Association is “dedicated to preserving the memory, commemorating the lives and restoring the honor of the 272 enslaved people sold by the Jesuits of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus in 1838.”

University of Virginia, President’s Commission on Slavery and the University

“At an April 2013 meeting of the President’s Cabinet, Dr. Marcus Martin, Vice President and Chief Officer for Diversity and Equity, made a presentation on slavery at UVa and proposed that a commission be formed to further explore the topic and to make recommendations as to the next steps the University could take in response to this history. Dr. Martin credited groups such as Memorial for Enslaved Laborers (MEL), the UVa IDEA Fund (Inclusion Diversity Equity Access), and University and Community Action for Racial Equity (UCARE) for creating robust initiatives around the topic of slavery, which will guide the Commission’s work. Slavery at the University of Virginia: Visitor’s Guide, a student-led brochure that provides visitors with information about the University’s history with slavery, is one such initiative. The formation of the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University is the next step in building a broader institutional effort.”

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Slavery and the Making of the University

“Slavery and the Making of the University” introduces materials that recognize and document the contributions of slaves, college servants and free persons of color primarily during the university’s antebellum period. Part of a larger project that included a physical exhibit mounted in the Manuscripts Department of Wilson Library October 12, 2005 through February 28, 2006 and a printed bibliography of sources, this online exhibit includes digitized images and transcriptions of many of the items from the physical exhibit as well as other items from the bibliography of sources not originally exhibited due to lack of physical space.”

Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice

“In 2003, Brown University President Ruth Simmons appointed a Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice. The committee, which included faculty members, undergraduate and graduate students, and administrators, was charged to investigate and to prepare a report about the University’s historical relationship to slavery and the transatlantic slave trade. It was also asked to organize public programs that might help the campus and the nation reflect on the meaning of this history in the present, on the complex historical, political, legal, and moral questions posed by any present-day confrontation with past injustice. The Committee presented its final report to President Simmons in October 2006. On February 24, 2007, the Brown Corporation endorsed a set of initiatives in response to the Committee’s report.”

Princeton University Slavery Project

“Princeton University, founded as the College of New Jersey in 1746, exemplifies the central paradox of American history. From the start liberty and slavery were intertwined. Princeton educated leaders of America’s fight for independence and hosted the Continental Congress in 1783. But the University’s first nine Presidents all owned slaves, a slave sale took place on campus in 1766, and enslaved people lived at the President’s House until at least 1822. One professor owned a slave as late as 1840.

The Princeton & Slavery Project investigates the University’s involvement with the institution of slavery. It explores the slave-holding practices of Princeton’s early trustees and faculty members, considers the impact of donations derived from the profits of slave labor, and looks at the broader culture of slavery in the state of New Jersey, which did not fully abolish slavery until 1865. It also documents the southern origins of many Princeton students during the ante-bellum period and considers how the presence of these southern students shaped campus conversations about politics and race.”

Rutgers University – Scarlet and Black Project

“The Scarlet and Black Project is a historical exploration of the experiences of two disenfranchised populations, African Americans and Native Americans, at Rutgers University. Its initial work begins with Scarlet and Black, Volume 1: Slavery and Dispossession in Rutgers History, which traces the university’s early history, uncovering how the university benefited from the slave economy and how Rutgers came to own the land it inhabits.“

Columbia University and Slavery

“The Columbia University and Slavery project explores a previously little-known aspect of the university’s history – its connections with slavery and with antislavery movements from the founding of King’s College to the end of the Civil War. The website was “created by faculty, students, and staff to publicly present information about Columbia’s historical connections to the institution of slavery.”

Harvard University – Harvard and Slavery

“Under the leadership of University President and Lincoln Professor of History Drew Gilpin Faust, a range of scholarly, research, and engagement efforts are underway in order to more fully examine the history and legacy of slavery at Harvard. In April 2016, President Faust and Congressman John Lewis unveiled a plaque on Wadsworth House honoring four women and men — Bilhah, Venus, Titus, and Juba — who lived and worked there as enslaved persons in the 18th century. President Faust has also convened a faculty committee of historians from across Harvard to advise, research, and provide recommendations on University efforts and initiatives. The University hosted a national academic conference on March 3, 2017, which explored the relationships between slavery and universities, across the country and around the world.”

University of Mississippi (Ole Miss), Slavery Research Group

“…a group of University of Mississippi faculty and staff working across disciplines to learn more about the history of slavery and enslaved people in Oxford [Mississippi] and on campus.”

Coming to the Table

“…provides leadership, resources, and a supportive environment for all who wish to acknowledge and heal wounds from racism that is rooted in the United States’ history of slavery.”