How the results of genealogical DNA tests can alter conversations about race in the United States.

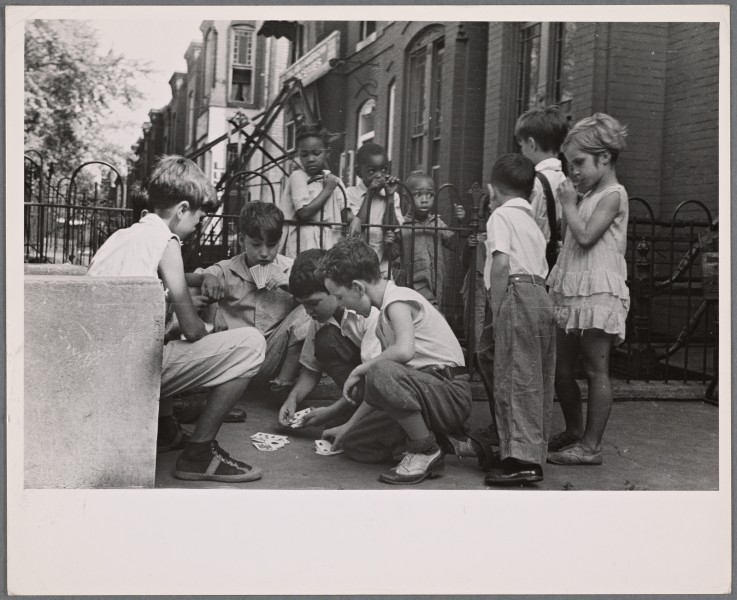

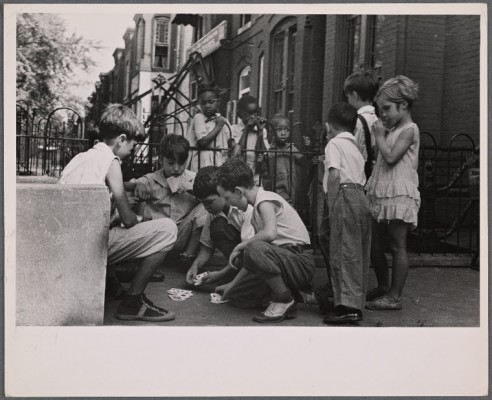

(Featured Image: Children playing cards in front yard in slum area near Union Station. Section inhabited by both whites and Negroes. Washington, D.C., Carl Mydans, September 1935)(1)

At their most basic level, DNA tests for genealogy are quite simple – A tube, spittoon, or swab used to collect saliva sent back to a lab for analysis, and weeks later, you’ve got answers about your ancestry through subjective percentages of ethnic groups reflected in your results. But, as the millions who have done these tests can attest, getting the results is just the preamble to a longer, more complex story.

The Great Equalizer

One the things I often bring up when I do presentations about genealogy and DNA is how I believe that the two are “The Great Equalizer.” Since we couldn’t control the circumstances or families into which we were born, genealogy and DNA brings us – regardless of class, race, or location – back to the same basic level: humanity. This is something that cannot be taken away. Ever. That mere fact levels the playing field for all who participate in genealogy and DNA. In my opinion, it’s one of the only things in life that can do what it does.

The Two Cousins Who Could

Back in June 2015, I was interviewed with my cousin, Crista Cowan of Ancestry.Com (The Barefoot Genealogist), during the Southern California Genealogy Jamboree. The interview was recently posted to Ancestry’s YouTube channel.

You read that right. We really are related. Not on a “It looks like we’re researching the same family line” or a “Well, our folks were in the same place around the same time” type of scenario. I’m talking a literal her mother falls amongst my highest matches on AncestryDNA.

Just five years ago we clearly checked different answers to question 9 on the 2010 United States Census.

For centuries African Americans have known what potentially lies behind their genome and about the situations that created me and Crista’s relationship. It’s hardly ever been a secret. It’s usually something that’s discussed openly. We may speak in hushed tones around folks of other races, but amongst ourselves, it’s usually full disclosure, even if a name is not known. Someone who was there passed the information to this generation, who passed it to that generation, and so on. It’s so prevalent that I notice many of the youth I work with are more interested in tracing their lineage of non-African descent than their lineage of African descent.

On the contrary, these conversations appear to be extremely rare when it comes to families of European descent. I can’t tell you the number of people I’ve had come to my conference sessions who talk about the discovery of their family passing or the fact that no one knew an ancestor was of African descent or a free person of color.

For some, the knowledge of these things or having a cousin of African descent is too much to bear. It’s so horrible that despite the fact that they’ve spent years posting and sharing all they’ve discovered online, they remove all traces these things after the discovery of cousins of African descent. Perhaps it’s a way to be disassociated from all of it.

Life, in a Picture

Just like the children in this photo by Carl Mydans, many African Americans who have taken genealogical DNA tests have stood on the sidelines watching their known relations of European descent. We’ve watched them play the game of genealogy and genetic genealogy like cards – wheeling, dealing, and holding research in their respective kitty – showing their hands to other researchers who look more like them, all the while noticing that we’re standing there, amongst their results and research, but they refuse to end the game or welcome us in.

There are some who stand on the fringes, like the kids in the back, who willingly come to the fence with information to help us, sometimes even reading the hands of the others and sharing the information, but they are far too few in number.

Perhaps some think it’s a crap shoot to find the relation. It’s possible they don’t want to anger other family members who may not be as open. Regardless, when information is not shared, whether it’s willingly withheld or not, it’s another way of stripping humanity away from people who deserve to have it.

A Perspective Shift

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

These are all names that many of us are familiar with because of the high profile nature of their deaths and the media coverage that ensued. But take a step back.

Imagine seeing these names, in the way they are displayed above, in your DNA results. Not because of some glitch in the system at 23andMe, AncestryDNA, or FamilyTree DNA, but because they’re actually your family. Your genomes match each other. You’ve got more than 5cM shared. You’ve got surnames and locations that match. You’ve got other DNA matches in common.

It’s not far fetched at all. It’s the reality that we, as Americans, live. It’s the remnant of the stain on our collective history and it’s something we can’t ever erase, get over, or forget.

If you were critical of the circumstances surrounding their deaths, would it change things if you knew they were family – the same blood running through your veins, the same progenitors living on the same land? Would you be more willing to be an ally for them with that knowledge? Should it take a death to make you more willing to advocate for them or will you do so beforehand?

Yes, their deaths have a connection with genealogy and the larger discussions on race. The same scores of folks who turn the other way when they hear about “another” incident with law enforcement involving the death of an African American are likely the same ones that scroll past their own relatives of a darker hue, hoping they’d disappear and that these DNA companies have played a cruel joke on them.

The fact remains that there is no joke. Ashton Kutcher is not coming out to tell you that you’ve been punked. This is real. Those faces are real. And every one of them could have been a relative of yours due to genetic serendipity.

Does this mean that you have to support all of their choices or actions that lead up to their deaths? No. You don’t do that with your known family.

On the other hand, the minute you begin to question whether or not anyone in their situation deserves to die, picture their faces among your DNA results. Will you continue to scroll past them and hope that they disappear, or will you honor the fact that beneath their skin, the had the same stuff inside that you do?

Sources

(1) Featured Image: The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Children playing cards in front yard in slum area near Union Station. Section inhabited by both whites and Negroes. Washington, D.C.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1935 Sept.. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/b152557d-2435-c4a5-e040-e00a180672a4

(2) Lopez, Mark Hugo, and Jens Manuel Krogstad. “‘Mexican,’ ‘Hispanic,’ ‘Latin American’ Top List of Race Write-ins on the 2010 Census.” Pew Research Center. Pew Research Center, 04 Apr. 2014. Web. 07 Jan. 2016. <http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/04/04/mexican-hispanic-and-latin-american-top-list-of-race-write-ins-on-the-2010-census/>.

Pingback: Friday Finds January 2 – 8 | Copper Leaf Genealogy