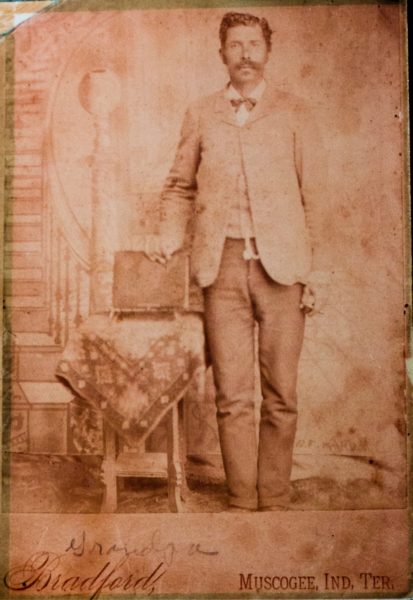

Was the murder of Isaac Rogers on April 20, 1897 really cut and dry? Read more as I weigh in on the murder of my great great grandfather, 120 years later.

Crawford “Cherokee Bill” Goldsby, was dead. It didn’t matter all the chaos he and his gang caused, he was never coming back. His family was grieved, but the community was relieved. The robberies and shootings were over. Life kept moving, but apparently Isaac Rogers, one of the men who made sure Bill was captured, wanted time to stand still for better or for worse. Clarence Goldsby, Bill’s brother, wanted no part of Ike’s plans. For more on Grandpa Ike, check out this earlier post I wrote about him, which details his role in the the capture of Cherokee Bill and I how discovered my relation to him.

Watch Those Freedmen Over There

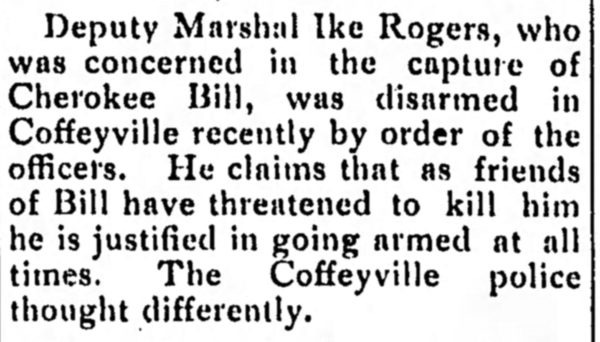

Catching outlaws is hard work and because of this, rewards were often given to those who could complete the job. Ike reportedly received $50 (equivalent to more than $1,400 in 2016) from a “prominent merchant of the Cherokee Nation.”1 The reward came with consequences though. Just months after the capture of Cherokee Bill, Ike began to fear for his life and was caught carrying a gun despite the fact that his commission as a U.S. Deputy Marshal had ended. The Coffeyville, Kansas Police were having none of it.2

In the Right Place at the Right Time

After Bill’s capture, and eventual hanging, the Cherokee Freedmen received their portion of a large sum of money (estimates are between $850,000 to $1 million)3 for the ceding of lands (known as the Cherokee Strip or Cherokee Outlet) belonging to the Cherokee Nation to the United States. Payments were dispersed in Hayden, Indian Territory in early 1897. Both Ike and Clarence stood to receive their share as one of up to 5,000 Cherokee Freedmen, but after many delays and growing frustrations within the community, things began to get tense. Notaries were charging upwards of $3 (equivalent to more than $87 in 2016) to sign identity affidavits and “thugs and swindlers”4 from all over were arriving to get a chance at becoming richer. It was so bad that the government sent troops. Naturally, with all that was going on, Hayden seemed like a prime opportunity for a tussle between Ike and Clarence and based on newspaper articles, it took place between February 1897 to April 1897.

Catch These Hands

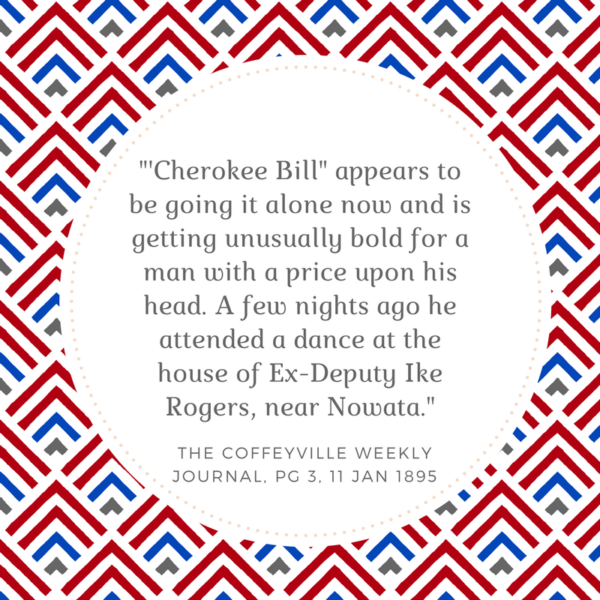

It’s clear from several accounts and family oral history that the Rogers and the Goldbsy families were more than acquaintances.5 Perhaps their familiarity is what lead to was a sense of betrayal on the part of the Goldsby family for Ike’s role in Bill’s capture. There was definitely enough fuel to light several fires and burn several egos.

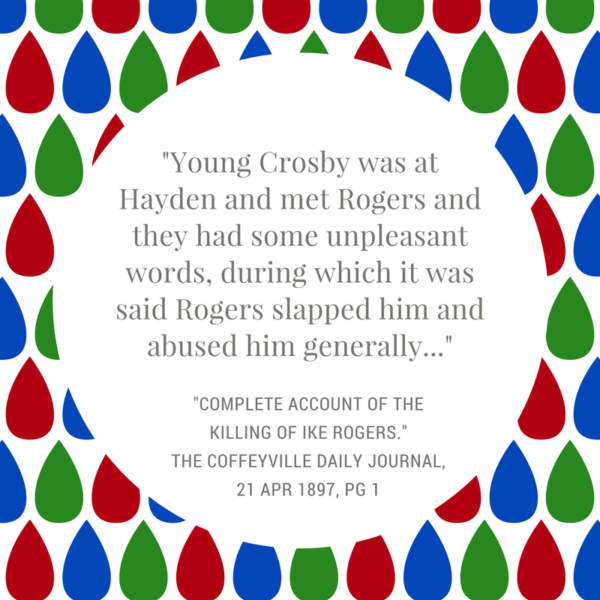

Reports vary as to exactly what happened during the Hayden tussle.

Harmon, S.W. Hell on the Border. Phoenix Publishing Company, 1898. Page 448. Accessed via Google Books.

…Clarence Goldsby, a younger brother of Cherokee, declared he would kill Rogers. At the payment at Hayden, Rogers is said to have questioned young Goldsby about this threat, even presenting a gun at his head and otherwise abusing him. The youngster was at the time unarmed, but informed Rogers that if he ever came to Ft. Gibson the killing would certainly be done. So the matter rested until Tuesday morning.6

Who was the true aggressor? What words were exchanged? Did Ike actually physically assault Clarence? Was Ike provoked based upon what he heard through the grapevine?

What’s clear is that Ike and Clarence did encounter each other and whatever happened, Clarence wanted Ike to know he was “not about that life.” In turn, Ike wanted Clarence to know he “wasn’t studying him.” It was a literally battle of testosteronic proportions.

“They Wonder How I Lived, With Five Shots…”

It is said the wife of Rogers telegraphed him not to go to Ft. Gibson but his confidence was supreme.6

The Coffeyville Daily Journal on April 21, 1897 reported that Clarence patiently waited for the train arriving at Fort Gibson carrying Ike to arrive every morning7. Ike stepped off acting normally and the Muskogee Phoenix noted he went about shaking hands. Then, the crime was committed. There was a huge crowd when Clarence fired the fatal shots. But just how many times was Ike shot?

“…Crosby [Goldsby] walked up to him and reaching over a woman’s shoulder, shot him through the neck with a 44, breaking his neck. When Rogers fell Crosby fired two more shots in his face, one through his left eye and the other just below it both passing clear through his head.”8 OK, he was shot three times.

“…when Goldsby advanced upon the back and right side of Rogers and shot him through the neck with a large revolver. Rogers gave a groan as he fell and Goldsby continued to advance and fire until five shots were fired.9 Wait, was he shot five times?

“Stretched on the platform, with a bullet-hole through his neck and three more through his head, lay Ike Rogers (colored), of Cooweescoowee, silent in death.”10 Now it’s four times?

“Ike Rogers, the man who captured Crawford Goldsby, alias Cherokee Bill, was shot three times at Fort Gibson, I.T., [today] by Clarence Goldsby, a brother of the desperado…”11 OK, maybe it was only three times?

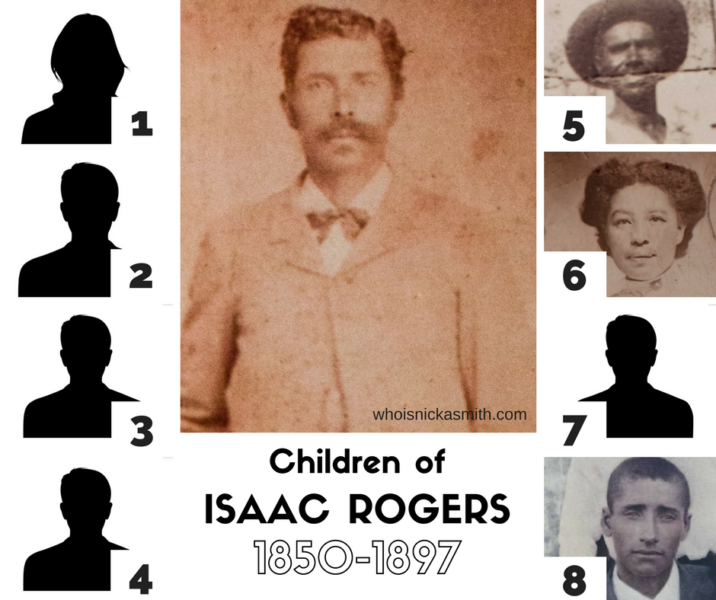

Even a deceased photo of Ike makes it hard to tell exactly how many times he was shot. (Click here if seeing photos of the deceased doesn’t gross you out). We may never know the accurate number of times he was shot, the fact is he was gone just like Bill, but he left a widow and eight known children behind. His youngest child was a day shy of turning a year old when he fell dead at Fort Gibson. His third oldest son died exactly six years after he did. Clarence Goldsby was never apprehended.

I was present at the depot platform at Ft. Gibson, Ind. Ter. on the 21st of April 1897 and witnessed the killing of this said Isaac Rogers by Clarence Goldsby. I saw the remains of Isaac Rogers after he was dead. I was the first man to him after he fell from the fatal shot by [Goldsby’s] gun. – Allen Lynch, July 20, 189712

The Aftermath

“The remains of the dead man were removed from the depot to the camp of the Freedmen, near the military post, prepared for burial and taken away on the evening train to the town of Nowata, near which place he resided.”13

Ike did not have a death certificate. At least one newspaper noted that a couple photographers were on hand the day the shooting took place, but efforts to locate their photos have come up empty except in the case where Ike was photographed deceased.

His wife and daughter are here and both are almost prostrated with grief.14

At the time of his death, Ike was married to the former Sarah Fry, daughter of Andy and Millie Fry, who were also Cherokee Freedmen. Sarah would remarry to Joseph Whitmire two years after Ike’s death. She died on June 16, 1902 which orphaned their three children at ages 16, 14, and 6 years old. The daughter mentioned could have been Ike’s youngest daughter, Ethel Jane, who would have been 11 years old at the time of his death, or his oldest daughter, Florence Rogers Bratcher, who would have been about 27 years old.

No known details seem to exist about where Ike’s funeral service took place or the events that happened there.

Oral history says that Ike is buried “10 miles south of the Kansas/Oklahoma border in a little town and cemetery named Lenapah.” Instructions to get there include “going south on Highway 169 to Nowata.”15 It’s been many years since family members have gone there. Is there a headstone? Which cemetery is it? There are still so many questions. Regardless, the events of April 20, 1897 still resonate in the Rogers family, although we’re all far removed from the wild tales of the Old West.

Known Children of Isaac Rogers (1850-1897), in birth order:

- Florence Rogers Bratcher, born about 1870, died unknown (Mother: Caroline James)

- Luther Clyde Rogers, born about 1873, died unknown (Mother: Caroline James)

- Eddie Rogers, born about 1878, died unknown (Mother: Alice Banks Rogers, married June 6, 1879)

- Nelson Vann Rogers, born about 1879, died April 20, 1903 (Mother: Sarah Vann Rogers, married between 1880-1884)

- Pictured: Theodore Cooey Vann Rogers, Sr., born January 10, 1883, died between 1922-1925 (Mother: Sarah Vann Rogers, married between 1880-1884)

- Pictured: Ethel Jane Rogers Reed, born August 25, 1886, died unknown (Mother: Sarah Fry Rogers Whitmire, married November 15, 1885)

- Raymond Andrew Rogers, born September 25, 1888, died unknown (Mother: Sarah Fry Rogers Whitmire, married November 15, 1885)

- Pictured: Roy McKinley Rogers, born April 21, 1896, died July 19, 1955 (Mother: Sarah Fry Rogers Whitmire, married November 15, 1885)

Note: Isaac Rogers also married to Ruth Vann Rogers on August 27, 1883. Ruth was the sister of Sarah Vann Rogers (mother of 4 and 5 above). They had no known children.

Interested in more from the Life After Death series? Click here.

Sources

(1) “The Territory.” The Weekly Star and Kansan (Independence, Kansas)22 Feb 1895, Friday. Page 2. Accessed via Newspapers.com.

(2) “Territory News.” Muskogee Phoenix, 19 Sep 1895, Thursday. Page 5. Accessed via Newspapers.com.

(3) “Pay the Freedmen.” The Leavenworth Times (Leavenworth, Kansas) 13 Feb 1897, Saturday. Page 1. Accessed via Newspapers.com.

(4) “Soldiers Ordered.” The Leavenworth Times (Leavenworth, Kansas) 17 Feb 1897, Wednesday. Page 1. Accessed via Newspapers.com.

(5) The Coffeyville Weekly Journal (Coffeyville, Kansas) 11 Jan 1895, Friday. Page 3. Accessed via Newspapers.com.

(6) “Killing of Ike Rogers.” Muskogee Phoenix (Muskogee, Oklahoma), 22 Apr 1897, Thursday. Page 5. Accessed via Newspapers.com.

(7) “Complete Account of the Killing of Ike Rogers.” The Coffeyville Daily Journal, 21 Apr 1897, Wednesday, Page 1. Accessed via Newspapers.com.

(10) “Worth Retelling – Killing of Ike Rogers at Fort Gibson Was Tragic.” The Wichita Beacon (Wichita, Kansas), 26 Apr 1897, Monday. Page 2. Accessed via Newspapers.com.

(11) Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, Virginia), 20 Apr 1897, Tuesday. Page 2. Accessed via Newspapers.com.

(12) General Affidavit of Allen Lynch, 20 Jul 1897, Indian Territory, Northern Distirct, Civil War Widows Pension of Isaac Rogers, Company E, United States Colored Troops 79th Regiment, application number 882523, certificate number 712932, filed from the Indian Territory.

(15) Rogers, Vaughn Curtis (1934-2008). Oral history interview, 20 January 2006.

![Bain News Service, Publisher. Pistols and Wax Bullets. , . [No Date Recorded on Caption Card] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ggb2004004329/. (Accessed April 12, 2017.)](https://www.whoisnickasmith.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/04329u-847x600.jpg)