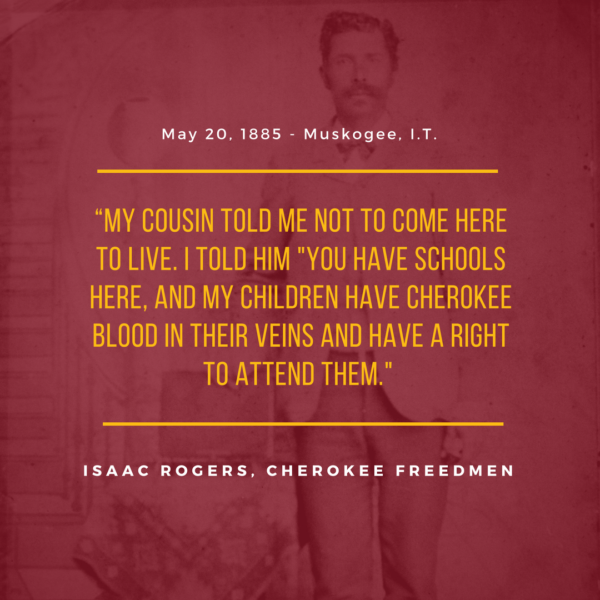

“My children have Cherokee blood in their veins…” Isaac Rogers, Cherokee Freedmen, May 20, 1885

On Wednesday, August 30, 2017, Cherokee Freedmen won our right to be admitted as full citizens of the Cherokee Nation. An appeal by the Cherokee Nation will not be coming as the Attorney General Todd Hembree states “While the U.S. District Court ruled against the Cherokee Nation, I do not see it as a defeat. As the Attorney General, I see this as an opportunity to resolve the Freedmen citizenship issue and allow the Cherokee Nation to move beyond this dispute.”

The 151 year battle has been long and arduous, and it’s most recent iteration played out across the terms of three U.S. presidents. In order to truly understand the magnitude of the decision rendered by U.S. District Judge Thomas Hogan, we’ll take a dive into the history of Cherokee Freedmen through the lens of my own family.

Behind the Brick Wall

Little Nan was my 5x great grandmother. I have no idea when she was born or what year she died, but I know that she gave birth to a son named Jesse “Checow” Rowe and lived during the 18th century and likely the 19th century. Little Nan was born in Georgia as evidenced by the Eastern Cherokee Application of her grandson Charles “Rab” Rogers who was the brother of my 3x great grandfather, Nick Rogers.1

Little Nan, her son Jesse, grandchildren, and extended family were enslaved by members of the Cherokee Nation. There were more than 1,000 people of African descent who were enslaved by the Cherokee as of 1828 and the number increased exponentially in the years that followed. Tales of “good slaveholders” abound in American genealogy and this is especially the case when it comes to the Five Civilized Tribes. Perhaps folks can’t fathom that one group marginalized for gain would in turn marginalize another group for gain, but that story has played out over and over throughout history worldwide.

In my research, it is almost impossible identify any differences between what was communicated about slavery by the Cherokee Nation versus what was communicated by slaveholders in the United States. The enslaved among the Cherokee were subject to slave codes. Here are a few:

- “That if any person or persons shall interrupt, by misbehavior (sic), any congregation of Cherokee, or white citizens, assembled at any place, for divine worship, such person or persons so offending, shall upon conviction, before any of the courts be fined in a sum not exceeding ten dollars, to be adjudged by the Court of the District in which such offense may be committed. And if any negro slave shall be convicted of the above offense, he shall be punished with thirty nine lashes on the bare back.”2

- “That any person or persons whatsoever, who shall trade with any negro slave without permission from the proper owner of such slave, and the property so traded for, be proven to have been stolen, the purchases shall be held and bound to the legal proprietor for the same, or the value thereof; and be it further resolved that any person who shall permit their negro or negroes to purchase spirituous liquors and vend the same, the master or owner of such negro or negroes shall forfeit and pay a fine of fifteen dollars for every such offense to be collected by the marshals within their respective districts for the national use; and should any negro be found vending spirituous liquors without permission from their respective owners, such negro, so offending shall receive fifteen cobbs or paddles for every such offense from the hands of the patrollers of the settlement or neighborhood in which the offense was committed, and every settlement of neighborhood shall be privileged to organize a patrolling company.”3

- “No person shall be eligible to a seat on the General Council, but a free Cherokee Male citizen, who shall have attained to the age of twenty-five years. The descendants of Cherokee men by all free women, except the African race, whose parents may be or have been living together as man and wife, according to the customs and laws of this Nation, shall be entitled to all the rights and privileges of this Nation, as well as the posterity of Cherokee women by all free men. No person who is of negro or mulatto parentage, either by the father or mother side, shall be eligible to hold any office of profit, honor or trust, under this Government.”

- All free male citizens (except negroes, and descendants of white and Indian men by negro women, who may have been set free,) who shall have attained to the age of eighteen years, shall be equally entitled in vote at all public elections.”4

If that wasn’t enough, the following was written the official newspaper for the Nation, the Cherokee Phoenix:

“The Great Spirit, they say, first made the black man, but did not like him; he then made the red man; was better pleased with him, but not entirely satisfied, he then made white man, and was very much pleased with him. He then summoned all three in his presence. Near him were three great boxes, one containing hoes, axes, and other agricultural and working implements. In another were spears, arrows, tomahawks, &c. and in the third, books, maps, charts, &c. He called the white man first, and had him choose. He advanced attentively surveyed each of the boxes, passed by that filled with working implements, and drew near that in which were tomahawks, spears, &c. Then the Indian’s heart sunk within him. The white man however passed it, and chose that in which were books, maps, &c., Then they say the Indian’s heart leaped for joy. The red man was next summoned to make his choice. He advanced, and without any hesitation choose the box containing the war and hunting implements. The other box was therefore left for the black man. The destinies of each were thus fixed, and it was impossible to change them. They inferred, therefore, that learning was for the white man, war and hunting for the Indian, and labor for the poor negro.”5

So little was thought of the Cherokee enslaved that they had no rights just like their brethren who were enslaved in the United States. Their narrative is largely removed or an afterthought when the Trail of Tears is discussed. Little Nan’s slaveholder definitely transported her to the Cherokee Nation West, but whether or not it was voluntary or forced is still being researched.

It was inevitable that tensions would mount with the foundation laid. In November 1842, a slave revolt took place in which the Cherokee blamed Seminoles of African descent for the uprising instead of their long history of discrimination against their Freedmen. 5 years later, Nick would have my 2x great grandfather, Isaac Rogers, with Martha May, a woman of Cherokee, European, and African ancestry who was enslaved by Cherokee Alzira Price May.

Chaos to Emergence

As the Civil War began, the Cherokee Nation made their position known. They signed a Treaty of Friendship with the Confederacy in October 1861.

The Cherokee people and their neighbors were warned before the war commenced that the first object of the party which now holds the powers of government of the United States would be to annul the institution of slavery in the whole Indian country, and make it what they term free territory and after a time a free State; and they have been also warned by the fate which has befallen those of their race in Kansas, Nebraska, and Oregon that at no distant day they too would be compelled to surrender their country at the demand of Northern rapacity, and be content with an extinct nationality, and with reserves of limited extent for individuals, of which their people would soon be despoiled by speculators, if not plundered unscrupulously by the State.6

The writing was on the wall. The Cherokee appeared to feel the cause of the Civil War was a question of losing their culture and nationality, which included chattel slavery. Sound familiar?

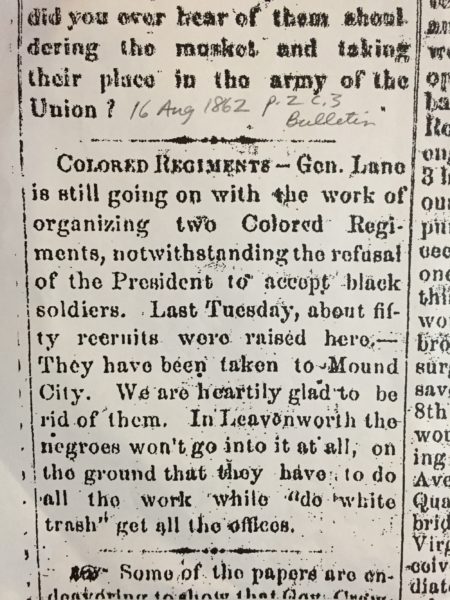

Isaac Rogers absconded from his Cherokee slaveholder and enlisted in the First Kansas Colored Infantry in Fort Scott on August 10, 1862. His unit, which eventually became the United States Colored Troops 79th Regiment, was one of the first that were enlisted and was the first to see battle in the Civil War. Less than two weeks after Isaac enlisted, Stand Watie, a staunch supporter of the Confederacy, became Principal Chief. Other family members, such as Isaac’s stepfather William Richardson and his uncle Charles Rab Rogers, enlisted in the Second Kansas Colored Infantry/USCT 83rd Infantry and the Second Indian Home Guards respectively.

Emancipation and the Seeds of Red Crow

The 13th Amendment abolished slavery within the United States but did not emancipate slaves held by the 5 Civilized Tribes. Freedom for the Freedmen could only be achieved through a treaty with the U.S. government. 8 months would separate when the formerly enslaved in the U.S. were legally free and when the Cherokee Freedmen were legally free.

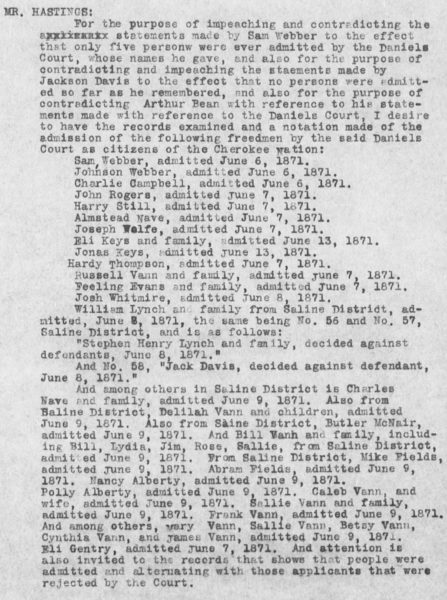

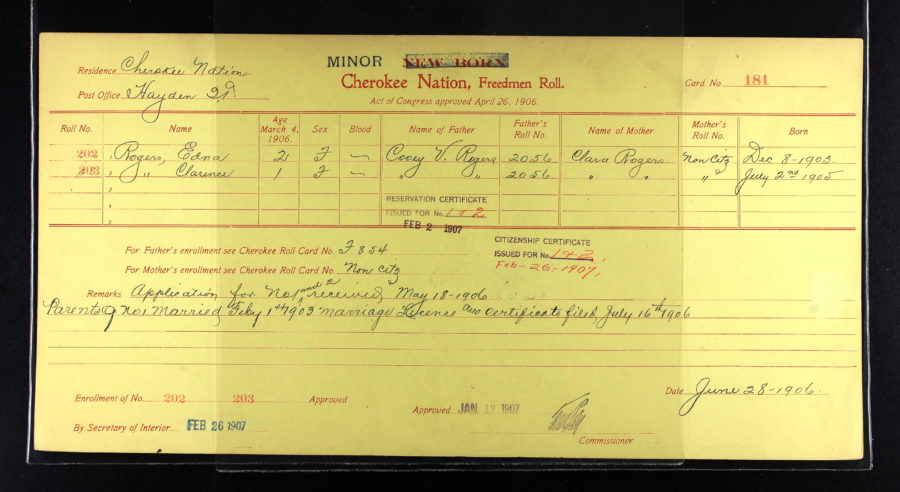

Article 9 of the Cherokee Treaty of 1866 officially abolished slavery within the Nation and stated “all freedmen who have been liberated by voluntary act of their former owners or by law, as well as all free colored persons who were in the country at the commencement of the rebellion, and are now residents therein, or who may return within six months [February 11, 1867], and their descendants, shall have all the rights of native Cherokees”7 At the time, most of my family was in southeastern Kansas which later exempted them from being eligible to be listed on the final Dawes Rolls. Only one ancestor would remain and be my ticket into the Nation, my 2x great grandmother Sarah Vann Rogers.

The Cherokee Freedmen were treated inconsistently. Some were allowed to vote in elections while others were not. Some went before the Cherokee courts to obtain a stamp of approval of their citizenship prior to the Dawes Commission and were approved while multitudes were not. As payments for land sales were disbursed to members of the Nation who fulfilled the blood quantum requirements, those same payments were not dispersed to the Freedmen despite the language in the 1866 treaty. Congress intervened but yet the Freedmen had to sue again and actively pursue their citizenship rights.

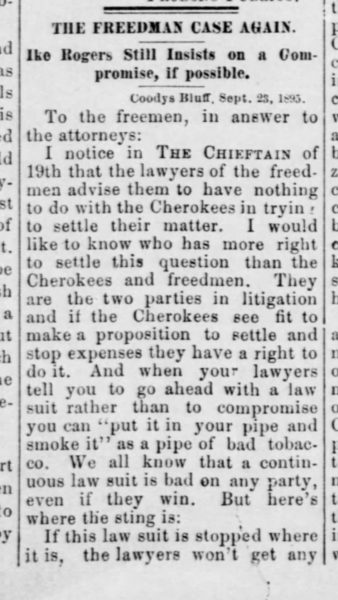

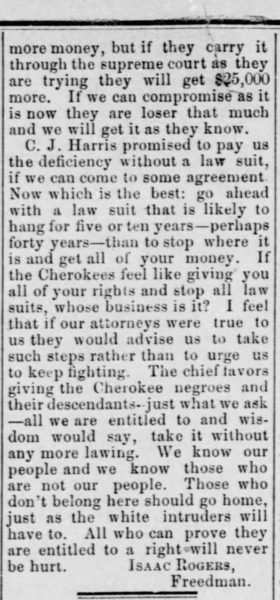

Things got so bad that the Committee on Indian Affairs came to the Nation to ask the Freedmen themselves how things were going. Isaac testified. My great grandfather, Theodore Cooey Vann Rogers, Sr. was the same age as my son as his father got up on the stand and indicted the Nation for mistreatment of their freedmen. Later, Isaac would write a letter to the editor of the Indian Chieftain calling for the two sides to come together to resolve the dispute which had been going on for nearly 30 years.8

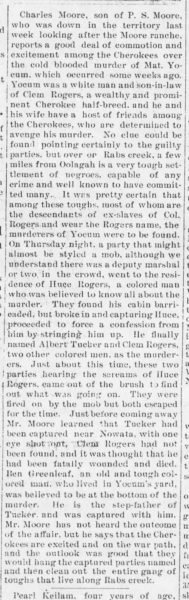

Eventually (after the Wallace Roll and Kern Clifton Roll) the Dawes Commission would come to pass ensuring the rights of but a portion of the Cherokee Freedmen. All the while vigilante justice was enacted, just like in the U.S, such as the time family members were accused of murdering the son-in-law of Clement Vann Rogers and were nearly lynched by the Cherokee. Rogers was the former slaveholder of their parents and father of humorist Will Rogers. Eventually, the dismissal of the charges would get nowhere near as much ink as their alleged deeds. Sound familiar?

Citizenship Unwound: The Lead Up to Wednesdays Decision

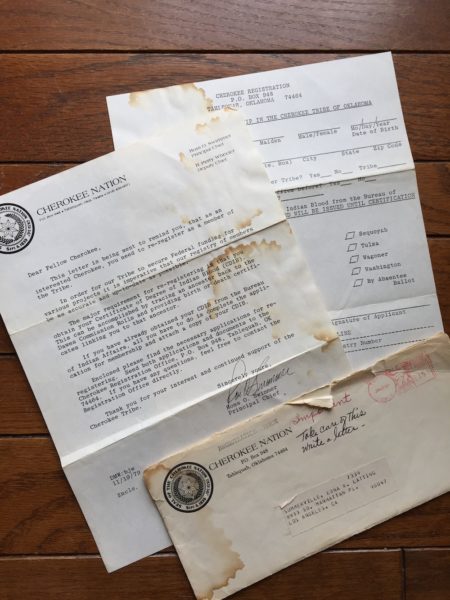

All of my grandmother’s siblings were registered members of the Cherokee Nation. Our family participated in elections, Freedmen groups, and maintained our land allotments for decades. Then, the mail stopped. My great aunt Edna received a letter stating “as an interested Cherokee, you need to re-register as a member of the Tribe.” It continued:

“In order for our Tribe to secure Federal funding for various projects it is imperative that our registry of members be as accurate and up-to-date as possible.

The major requirement for re-registering is that you obtain your Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood (CDIB). This can be accomplished by tracing an ancestor back to the Dawes Commission Rolls and providing birth or death certificates linking you to that ancestor.”

The problem was Aunt Edna didn’t have to do that. She was an ORIGINAL enrollee.

The letter was written the same year I was born, postmarked exactly two years before Aunt Edna died. My grandmother saved the letter from amongst her sister’s effects. A note “Important: Take care of this write a letter” was written on the envelope. For the last 19 years, I held onto the letter hoping and praying that one day I could “take care of this.”

After 34 years, prompting from Marilyn Vann, and six attempts at sending in my own application last year, it’s finally taken care of. Finally. For the longest time I didn’t even want to pursue membership, but I came to the conclusion it’s my birthright. And I’m going to take it. All 8 generations. Period.

Sources

(1) Rogers, Rob (21150), page 5. Eastern Cherokee Applications of the U.S. Court of Claims, 1906-1909. Accessed 31 Aug 2017 via Fold3.com.

(2) “GENERAL COUNCIL OF THE CHEROKEE NATION. NATIONAL COMMITEE (sic) , Monday, Nov. 10.” Cherokee Phoenix Transcription. Western Carolina University, 19 Nov. 1828. Web. 28 Apr. 2017. <http://www.wcu.edu/library/DigitalCollections/CherokeePhoenix/Vol1/no38/pg1col4b-5bPg2col1-2b.htm>.

(3) “CHEROKEE LAWS. [Continued] New Town, Oct. 28, 1829.” Cherokee Phoenix Transcription. Western Carolina University, 10 Apr. 1828. Web. 28 Apr. 2017. <http://www.wcu.edu/library/DigitalCollections/CherokeePhoenix/Vol1/no08/cherokee-laws-page-1-column-1b.html>.

(4)”CONSTITUTION OF THE CHEROKEE NATION,.” Cherokee Phoenix Transcription. Western Carolina University, 21 Feb. 1828. Web. 28 Apr. 2017. <http://www.wcu.edu/library/DigitalCollections/CherokeePhoenix/Vol1/no01/pg1col2a-pg2col3a.htm>.

(5) “CURIOUS INDIAN TRADITION.” Cherokee Phoenix Transcription. Western Carolina University, 29 July 1829. Web. 28 Apr. 2017. <http://www.wcu.edu/library/DigitalCollections/CherokeePhoenix/Vol2/no17/pg2col2a.htm>.

(6) “Cherokee Declaration of Causes (October 28, 1861).” Cherokee Nation. N.p., n.d. Web. 31 Aug. 2017. <http://www.cherokee.org/About-The-Nation/History/Events/Cherokee-Declaration-of-Causes-October-28-1861>

(7) “Treaty with the Cherokee, 1866.” INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES. Vol. 2, Treaties. Oklahoma State University Library, n.d. Web. 31 Aug. 2017. <http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/vol2/treaties/che0942.htm#mn17>.

(8) “The Freedmen Case Again.” Thursday, 26 Sep. 1895, The Weekly Chieftain (Vinita, Oklahoma), page 2. Accessed via Newspapers.com 28 Apr 2017.

Cousin this is so amazing and words can’t describe how I feel to see the picture of my father, granddaddy, grandma and my gamma with the family so beautiful. I love all the history you have found out about our family. I use to ask but gamma only told me bits and pieces of everything because I was to young to understand. I miss them all so much. Thank you for all your knowledge and research. Thank you.

Hey Cuz! I’m so glad you found this! We have an amazing family history. Whatever you do remember, share it! We all have different pieces of it. I’d love to hear it!

Excellent, I wanted to know if you know more about the Vanns as listed in the excerpt you posted about the Court hearings of 1871. my 6xgrandfater and mother Caleb and Sallie Vann were admitted to the Rolls.

They were owned by Rich Joe Vann. I think Sallie was at least Half Cherokee or more. Thank you very much.

CJCarter

It’s amassing you’re telling my story my 5x grandfather Charley Rogers I’m having problems with his mother Sydney Ross rogers father John brown is in Cherokee nation but it won’t show which John brown