Hold tight before passing out the cigars and pouring the champagne for obliterated brick walls when it comes to the Freedmens Bureau Records.

It’s been touted as the most important record set for African American genealogy and FamilySearch set out to index it and make it available online. Announced on Juneteenth 2015, the Discover Freedmen project aimed to digitize and index over 1.5 million records created by the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands. The hope was that it would “reunite the black family that was once torn apart by slavery.”(1)

Fast forward a year later, and thanks to volunteers, the indexing part of the project is complete – although the definition of complete is subject for debate – and some of the records have already been released online. This week, one of the larger pieces of the collection, the labor contracts, were made available to the public for the first time in an en masse indexed format. These contracts were between former slaves and planters and were created to ensure that the Freedmen were paid for work their work as new citizens and that the interests of both parties were protected. They can include the name, age, sex, wage earned and other details of the formerly enslaved and the name and location of the plantation, and its owner, who could be the former slaveholder of those on the contract. FamilySearch’s version of this collection also includes indenture and apprenticeship records. States featured are Alabama, Arkansas, District of Columbia, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia.

I have read through thousands of labor contract images over the last 17 years. I had no choice really. Not until recently had anything been put online, so I did it the old way – using microfilm going largely page by page – and came across some records for ancestors who were formerly enslaved but not the lion’s share that seems to have been promised through this project. I was eager to see what would happen once the index was created.

So, there I went, entering in names and searching. I started with records I knew were in the collection to see how they were captured. For some reason, the locations that I knew these records were created in were not listed in the index. The larger metropolitan area was listed instead.

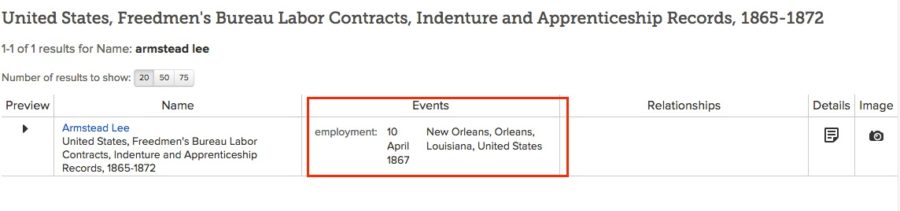

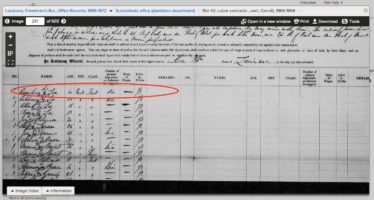

For instance, consider Armstead Lee, my 3x great grandfather who I discovered and documented through the series Finding John Lee. I had found a labor contract between him and J.E. Lewis & Company who owned Kerr Plantation in Carroll Parish, Louisiana dated April 10, 1867 back in 2010. When I searched FamilySearch’s United States, Freedmen’s Bureau Labor Contracts, Indenture and Apprenticeship Records, 1865-1872, the following is noted:

New Orleans, Louisiana and Carroll Parish, Louisiana are 257 miles away from each other. As you can see, there is no other record noted with Armstead Lee, at least spelled in that way. I then checked to see if the image that I had found previously was the same one on the FamilySearch website.

This was indeed the same record I had found on microfilm in 2010.

If I had been a new researcher, I probably would have disregarded this record. I would have assumed that there was no way the person listed was my ancestor due to the distance between where my ancestor was heavily documented and where this document was allegedly created.

Unfortunately, despite all the hours that volunteers have put into these records, the methodology used in indexing them could make the indexes useless. The point of creating the index was to cut the time needed going page by page to find ancestors, but if the locations for the records aren’t correct once search results are rendered, a researcher is still going page by page.

Additionally, The Bureau wasn’t just for the formerly enslaved or Freedmen – it operated for refugees, which were displaced people of European descent, and it operated for abandoned lands. This means that there could potentially be ancestors of those of European descent who aren’t indexed in the correct locations either.

After locating the instructions for volunteers, I noticed that they weren’t given instructions about locations, so it appears as though locations may have been arbitrarily chosen based on the roll of microfilm they came off of. These records were organized by state into record groups created by the National Archives. That’s all good and well in that environment, but for a researcher, displaying the right location is key when getting search results.

Once I discovered this issue, I posted about it on my Facebook page.

Several other people tested out this theory and came up with the same result. I’m really hoping that this can be rectified or at least some primer or communication can go out clarifying things. Otherwise, this record set may not be as useful as it could be.

Don’t miss the latest! Subscribe by email.

Don’t miss the latest! Subscribe by email.

Click here to subscribe to Who Is Nicka Smith

Click here to subscribe to The Lowdown by BlackProGen

Sources

Featured image: Bain News Service, Publisher. Negro Singing and Dancing Group. [no Date Recorded on Caption Card] Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <https://www.loc.gov/item/ggb2006007998/> 26 Aug 2016.

(1)Walch, Tad. “LDS Church, FamilySearch Launch Project to Index Freedmen’s Bureau Records of 4 Million Former Slaves.” DeseretNews.com. N.p., 19 June 2015. Web. 26 Aug. 2016. <http://www.deseretnews.com/article/865631024/LDS-Church-FamilySearch-launch-project-to-index-Freedmen7s-Bureau-records-of-4-million-former.html?pg=all>.

(2) “United States, Freedmen’s Bureau Labor Contracts, Indenture and Apprenticeship Records, 1865-1872,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2W3-F56C : accessed 26 August 2016), Armstead Lee, 10 Apr 1867; citing Employment, New Orleans, Orleans, Louisiana, United States, NARA microfilm publication M1905, Records of the field offices for the state of Louisiana, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, 1863-1872 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 42; FHL microfilm 2,426,097.

I recently had a phone conversation with someone (a “highly placed person” with knowledge of this project, whom I’m being polite enough not to out) at FamilySearch.org, and while the problems you’ve noted are bad, they are just scratching the surface when it comes to comparing what the publicity says these records are and the reality. One of the big things touted was that the complete set of Freedmen’s Bureau records would be indexed. Guess what — they weren’t. Due to pressure from the Smithsonian, the field office records were never part of the project; most of them are still unindexed and must be searched manually. So of the 30 Freedmen’s Bureau databases on FamilySearch.org, only 15 have an index. That’s an unusual definition of “everything.” (One small sliver of hope: FamilySearch is still considering whether to have the field office records indexed. I strongly recommended doing so.)

Another problem — as you mentioned, Nicka, the National Archives microfilms had the records sorted by state. Now, all the labor contracts are in one “United States” database, and the same for school records, hospital records, etc. So if the state that the Freedman was living in didn’t actually appear on the record but another state did (and yes, some of the records are like that, like a contract where the person hiring is in a different state), that record will only appear under the second state, not the one that the person was living in. Most of the time a researcher isn’t going to check a record that lists the wrong state, so that’s a bunch of people who are now harder to track down.

Something else that hasn’t been publicized well is how the search works now for the records. If you go directly to FamilySearch.org, as I did at first, you will need to search through each database individually. If you go to DiscoverFreedmen.org, the very, very basic search on that page (all it lets you input is first and last names, so it looks next to useless) actually searches all 15 indexed databases at once. But don’t pay attention to the short list of 20 results you’ll see on the DiscoverFreedmen page. Click the link that says it will show you all the results. That will take you to FamilySearch.org, and along with letting you see more than 20 results at a time, you’ll get to see which databases the results came from. You can delete databases if you don’t think the locations will be relevant, but considering the whole location problem discussed above, do so with caution.

And yet another problem with the index: From the beginning, the instructions given to volunteers were not to transcribe every name on a record. No, someone at FamilySearch and/or the Smithsonian decided that Bureau employees weren’t worthy of being recorded, and some other people’s names also were not included in the index. So the index is not really an every-name index for these records.

The good news is that even a flawed index is better than no index, and the Freedmen’s Bureau records are far more accessible than they used to be. But the flaws need to be understood so that researchers will know when not to put all their faith in that index.